No Place Like Home

June 29, 2018

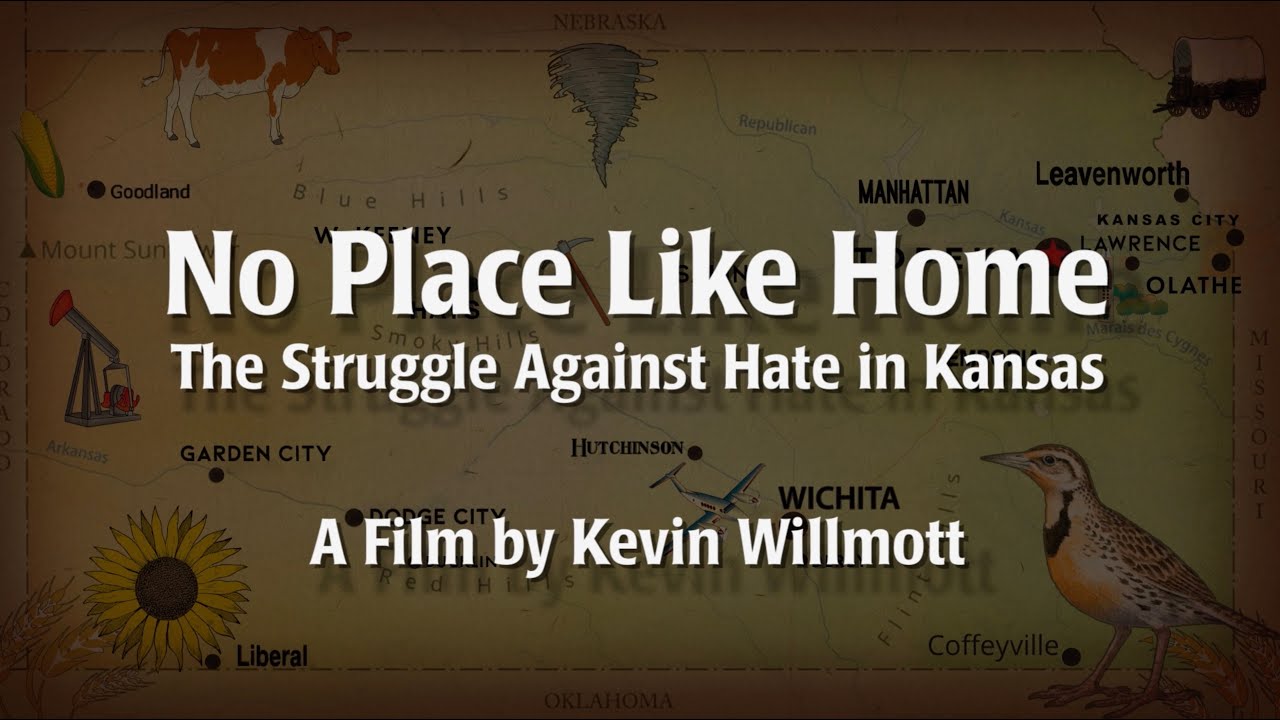

Father of the gay rights movement and first openly gay elected official in the country Harvey Milk (1930-1978) once said, "If every gay person were to come out only to his or her own family, friends, neighbors and fellow workers, within days the entire state would discover that we are not the stereotypes generally assumed." Author C.J. Janovy wrote No Place Like Home: Lessons in LGBT Kansas (University of Kansas Press, 2018) in part to debunk stereotypes about both Kansas and the LGBTQ people living here. Humanities Kansas recently awarded Do Good Productions of Leawood a Humanities for All grant in support of a short film based on No Place Like Home. The film is directed by Oscar winner Kevin Willmott and narrated by Melissa Etheridge and explores the history of the LGBTQ movement in Kansas and sparks meaningful discussion on the topic.

Watch the No Place Like Home trailer

In the book No Place Like Home, Janovy echoes Milk's sentiment decades later and half a continent away from the California of which he was speaking. She writes, "out here, the hard work of changing hearts and minds falls to individuals who carry it out family member to family member, neighbor to neighbor, coworker to coworker." In this excerpt from chapter 5 "Pioneers in Western Kansas" we meet one of these individuals.

Excerpt from No Place Like Home: Lessons in Activism from LGBT Kansas by C.J. Janovy

Copyright University Press of Kansas. Reprinted with permission. www.kansaspress.ku.edu.

From Chapter 5: Pioneers in Western Kansas

Leonard Kahl was a strapping farmhand whose marriage had gone sour. Kahl was forty. He’d lived his whole life in Malvern, Iowa, a town of about a thousand people, driving a tractor since he was seven and struggling with something else for almost that long. During his annual physical before eighth grade, Kahl mentioned his feelings of being a girl to his family doctor. “He says, ‘Oh, you grow up, get married, have kids, and they’ll go away.’ That SOB. I’d like to find him and kick his butt, because the feelings never go away.”

Kahl followed the doctor’s instructions, getting married right out of high school, having a son and then a daughter. The feelings persisted, so Kahl visited libraries and learned more about them. On rainy days when he couldn’t do farm work, he would drive up to thrift stores in Omaha, Nebraska, or Council Bluffs, Iowa, and buy women’s clothes, which he would hide at home to wear whenever he could. His wife always found his stash. He would throw it all out and vow it wouldn’t happen again, but that lasted only a few months. “I tried and I tried. I was married for twenty-three years. I saw my son grow up and move on. My daughter was fifteen. I was unhappy as hell.”

One day, it was Kahl’s daughter who discovered the lingerie. “The crap kinda hit the fan,” said Kahl, who confided in his sister, who had a former college roommate in Kansas who was going through a divorce and looking for someone to run the family farm. “I opened up to her quite a bit,” Kahl said of this family friend. “She joked, like, ‘You’re not going to go into the local co-op in a dress and heels, are you?’ I told her, ‘Oh, hell, no. I have things to work out, but I can take care of your farm.’ I packed what I could get in the back of the truck and moved.” Destination: the fortuitously named Haven, population 1,200. Leonard left for Kansas to become LuAnn.

"out here, the hard work of changing hearts and minds falls to individuals who carry it out family member to family member, neighbor to neighbor, coworker to coworker."

The boss lady lived ninety miles away, so Kahl had an old five-bedroom farmhouse to herself. The farm was a mess, but after a year, Kahl had it straightened out. Then she needed to pay more attention to herself. One night she drove to Wichita and found a copy of an LGBT magazine called the Liberty Press, where she saw an ad for a doctor who agreed to help. By spring 2003 Kahl was taking female hormones.

She let her blonde hair grow out and wore it in a ponytail. “I really wasn’t paying a whole lot of attention to the fact that I was developing boobs until one day, it was hot as hell, and the center pivot irrigation motor broke down.” With the heat threatening to burn the crops, Kahl drove to town in a hurry. “I walked into this parts store and the fella says, ‘Can I help you, ma’am?’” Kahl was dumbfounded. “I had on this sweaty T-shirt and the girls were showing through plenty. I thought, ‘Maybe I should work on this transition thing better.’ I went to Walmart the next day and bought some bras that fit properly.” If getting called ma’am was a shock, it was also a morale booster. “When I made runs to town,” Kahl said, “I tried to start looking a little more feminine.”

After a while the irrigation system needed more repairs. Kahl and the boss lady met in town at the dealership. Now Kahl was wearing a tight T-shirt and jeans that showed her feminine figure, and she was trying to work on her voice, which was deep enough to match her six-foot frame. The boss introduced her to the irrigation salesman as Leonard. “Afterwards she says, ‘We have to talk. I thought you were more of a cross-dresser. But you want to become a woman.’ I says, ‘Yeah.’ She says, ‘I would love for you to stay, but I’m worried about what people would say.’” There was another problem: post-divorce, the owner wasn’t making enough money to keep the farm.

Kahl had been thinking it was time to move on anyway. She put an ad in Dodge City’s High Plains Journal. “Experienced farm help looking for a job,” was all it said. She got calls from all over, and was hired on with a father and son in the unincorporated community of Kalvesta, just a grain elevator and a handful of houses thirty-two miles from any town with a grocery store. “They questioned me about the long hair, but other than that, I think they were hard up for help they could trust.”

Reading the Liberty Press as she prepared to move out of Haven, Kahl learned about an upcoming meeting of LGBT people in Dodge City. The woman who had called the meeting was named Anne Mitchell. She had moved to Kansas from Berkeley – yes, that Berkeley. Mitchell was working as a legal secretary in downtown San Francisco in the late 1980s when she and a college friend decided it would be fun to meet in Kansas City and drive out to visit another college friend who was managing cattle in the Flint Hills. On the trip, Mitchell met a woman who owned a ranch in Comanche County along the stark Oklahoma border, and fell in love not only with the woman but also with the landscape.

Mitchell went to graduate school at the University of Kansas and earned a degree in clinical social work. Then, from the ranch, she would drive to counseling jobs in sparsely populated counties. “You do crisis work at all these little mental health facilities, go out and screen suicidal cowboys.” She sat with good Christian parents who had made their daughters get abortions, or people who could cope with their ostensibly idyllic small-town lives only with massive amounts of Xanax. “You hear what people say out in public,” Mitchell said, “but you know the truth.”

Mitchell was devastated when 70 percent of Kansas voters banned same-sex marriage in 2005, and when someone asked if she’d be willing to start a Southwest Kansas chapter of the new statewide advocacy group called Equality Kansas, she agreed.

Mitchell invited everyone she could think of who was slightly progressive to supper at the western-themed Dodge House Restaurant on West Wyatt Earp Boulevard. Eighteen people showed up. Among them was Lindy Duree, a fifty-something reading teacher at Dodge City Middle School who had been troubled by other teachers’ response when a student confessed to one of them that he was gay. “They kept saying, ‘What are we going to do with this kid?’”

Duree headed to the Dodge House. “I sat down at a table with two very nice ladies.” Across the table, she recognized a former student. Then, Duree said, “I realize the two ladies I’m sitting with are not ladies.” Afterward, Duree’s former student came over. “He said, ‘Mrs. Duree, I didn’t know you were gay.’ I said, ‘I’m not, and I didn’t know you were.’ After that, I came home and said to my husband, ‘You need to meet these people – they are fun.’”

C.J. Janovy is a veteran journalist in Kansas City, currently at KCUR (the city's NPR affiliate). Prior to that she spent a decade as editor of the local alt-weekly, The Pitch. She lives with her wife.